Mardi Gras

with ORO VALENTIO

The Tuesday before Ash Wednesday

Culturally, Mardi Gras serves as a threshold. It is not meant to extend indefinitely, but to conclude. The revelry of the day gives way to Ash Wednesday, where reflection, repentance, and renewal begin. This deliberate contrast preserves meaning on both sides: celebration retains its depth because it ends, and discipline retains its humanity because it is preceded by joy.

At its core, Mardi Gras is not about indulgence for its own sake, but about recognizing rhythm—honoring the human need for festivity while affirming the greater necessity of restraint, clarity, and renewal. It stands as a reminder that celebration is most meaningful when it knows its place, and that true joy is not diminished by discipline, but given its proper time and purpose.

Joy is NOT the Opposite of Sacrifice

Mardi Gras reflects a deep truth about both human nature and the wisdom of tradition: that joy and sacrifice are not enemies, but companions—each giving meaning to the other when rightly ordered. Joy, rightly understood, is not a flight from duty, but a strengthening of the heart before it is called to bear the weight of sacrifice. Celebration, when given its proper time and meaning, reminds us why self-denial matters, and what it is ultimately for. Far from numbing the soul, ordered joy stirs gratitude, forges connection, and restores vision—so that sacrifice can be embraced not with bitterness, but with conviction and love.

Historically, this rhythm prevented both extremes. Without joy, sacrifice becomes harsh and brittle; without sacrifice, joy dissolves into excess and emptiness. Mardi Gras stands precisely at this balance point. It allows laughter, color, music, and shared festivity to have their rightful place, while clearly signaling that they are not the final aim. When the celebration ends, it does not leave behind exhaustion or denial, but readiness. The heart, having tasted abundance and community, is better prepared to embrace restraint, reflection, and self-giving.

In this way, Mardi Gras reveals that joy is not the opposite of sacrifice—it is its preparation. It shows that discipline grounded in gratitude is stronger than discipline born of mere denial, and that when joy precedes it, sacrifice becomes not a burden, but a gift of love freely given.

Mardi Gras Traditions to Make Your Own

1. Wearing Masks and Costumes

Rooted in medieval Carnival, masks allow revelers to be anonymous and equal for a day.

In New Orleans, elaborate feathered masks and costumes are a staple—sometimes required by law for float riders.

2. Parades

Floats roll through city streets, often themed and sponsored by krewes (social clubs).

Parades often include:

Marching bands

Dance troupes

Costumed performers

Giant floats

3. Krewe Culture

Krewes are private clubs that organize parades and balls.

Each krewe has its own theme, history, royalty (king and queen), and signature “throws.”

Famous krewes: Rex, Zulu, Bacchus, Endymion, and Muses

4. Throws

Beads (purple, green, and gold)

Doubloons (custom coins)

Cups, toys, and handmade items (like Muses’ decorated shoes or Nyx’s purses)

The goal? Catch as much as you can!

🍰 Traditional Foods

5. King Cake

A colorful, circular pastry decorated in purple, green, and gold sugar.

Hidden inside is a tiny plastic baby (symbolizing Jesus or luck).

Whoever finds the baby must buy the next cake or host the next party.

6. Rich, Fatty Foods

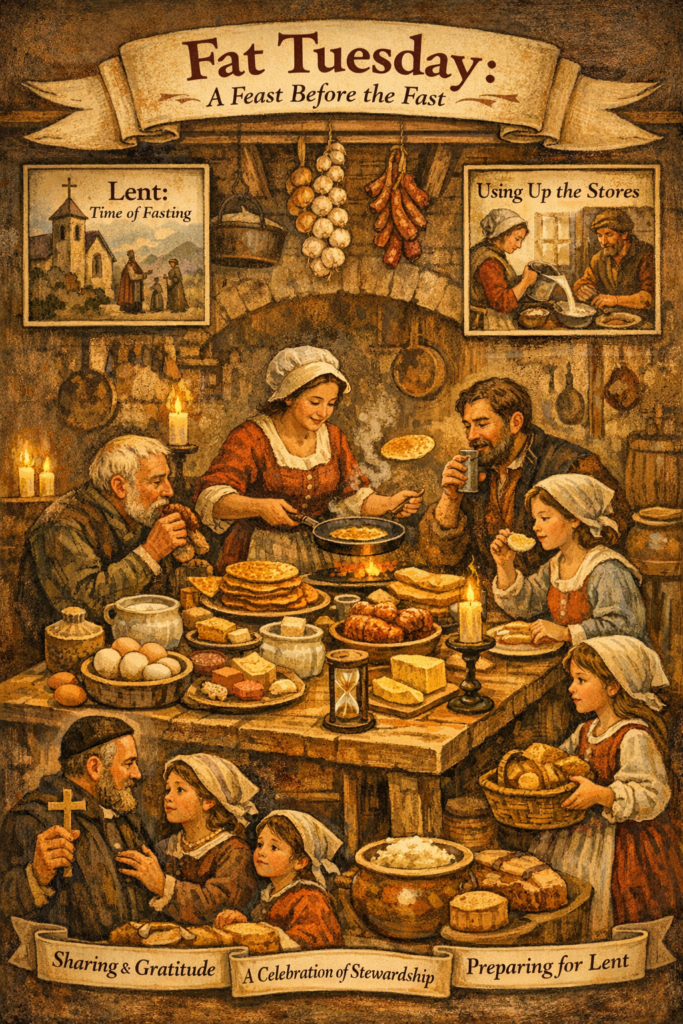

Mardi Gras means “Fat Tuesday,” the last day to indulge before Lent.

Foods vary by culture but often include:

Fried foods, meats, cheese, butter, and pastries

Pancakes or crêpes (especially in the UK and France)

🎉 Music and Dancing

7. Brass Bands and Jazz

Especially in New Orleans, Mardi Gras is filled with live jazz, funk, and brass bands.

Street parties and second line parades (impromptu processions) are common.

8. Mardi Gras Balls

Formal events hosted by krewes

Often include debutante-style presentations, with kings, queens, and elaborate gowns and pageantry

⛪ Religious and Historical Traditions

9. Fat Tuesday as Pre-Lenten Celebration

Mardi Gras is the final day before Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent.

It originated as a way to use up rich foods before the fasting season.

10. Burning of the Boeuf Gras

Historically, a live fatted ox was paraded to symbolize the end of meat before Lent.

Today, Boeuf Gras may be represented as a float or symbol in Rex parades.

✨ Color Symbolism

11. Purple, Green, and Gold

Chosen by the Rex Krewe in 1872:

Purple = Justice

Green = Faith

Gold = Power

🌍 Mardi Gras Around the World

12. Carnival (Brazil, Italy, etc.)

Brazil: Samba parades, sequins, massive floats

Venice: Elegant masquerade balls and baroque masks

France: Parades, crêpe feasts, and burning of effigies

13. Shrove Tuesday (UK, Canada, Australia)

Known as Pancake Day

Traditional pancake races and feasts

May the Joy We Share Today be Rightly Ordered

May the joy we share today be rightly ordered,

tempering abundance with gratitude and care.

As we finish what has been given,

may our hearts be readied for discipline,

our homes for simplicity,

and our lives for deeper love and faithfulness.

Let this day’s gladness prepare us—not distract us—

so that, in honest joy,

we may enter Lent with strength, humility, and peace.

Mardi Gras Cake & Decorating Ideas

This section is meant to be more than Cake Decorating Ideas… it’s designed to spark inspiration and creativity, awaken tradition, and infuse your special occasions with style, identity, and atmosphere. A color palette becomes a theme. A design becomes a mood. Simple details—like sugared holly leaves or shimmering stars—can set the tone for a gathering and become part of cherished traditions and lasting memories melded with personal touch and love.

Traditional Mardi Gras Dishes

Traditional Mardi Gras Foods

New Orleans (Louisiana Creole/Cajun Traditions)

New Orleans (Louisiana Creole/Cajun Traditions)

1. King Cake

1. King Cake

The most iconic Mardi Gras food.

A sweet, ring-shaped brioche or cinnamon roll-style pastry.

Topped with icing and colored sugar: purple (justice), green (faith), gold (power).

Often contains a hidden baby figurine—whoever finds it hosts the next party or buys the next cake.

2. Gumbo

2. Gumbo

A rich stew made with roux, vegetables (the “holy trinity”: onion, celery, bell pepper), and meats or seafood.

Often includes sausage, chicken, shrimp, or crab.

3. Jambalaya

3. Jambalaya

A spiced rice dish cooked with meat, seafood, vegetables, and Creole seasonings.

4. Étouffée

4. Étouffée

A smothered, saucy dish usually served over rice.

Popular with crawfish (crawfish étouffée), shrimp, or crab.

5. Fried Seafood

5. Fried Seafood

Fried shrimp, oysters, or catfish—served with remoulade or po’boy-style.

6. Po’ Boys

6. Po’ Boys

Classic New Orleans sandwich on French bread, filled with fried shrimp, oysters, or roast beef, and dressed with lettuce, tomato, pickles, and mayo.

7. Red Beans and Rice

7. Red Beans and Rice

A Monday tradition in New Orleans, but commonly served during Mardi Gras week.

Cooked with ham hocks or andouille sausage.

8. Hurricanes & Other Cocktails

8. Hurricanes & Other Cocktails

Fruity and potent, the Hurricane is made with rum, fruit juice, and grenadine.

Other favorites: Sazerac, French 75, or classic daiquiris.

International Mardi Gras / Carnival Foods

International Mardi Gras / Carnival Foods

France

France

9. Crêpes or Pancakes

9. Crêpes or Pancakes

Eaten on “Shrove Tuesday” (called Mardi Gras in France).

Made with butter, eggs, and milk—rich ingredients traditionally forbidden during Lent.

10. Beignets

10. Beignets

Deep-fried dough covered in powdered sugar.

In New Orleans, they’re a year-round favorite, but especially festive during Carnival.

Brazil (Carnaval)

Brazil (Carnaval)

11. Feijoada

11. Feijoada

A rich black bean stew with pork, rice, collard greens, and orange slices.

12. Brigadeiros

12. Brigadeiros

Chocolate truffles made with condensed milk, cocoa, and butter.

Italy

Italy

13. Frittelle / Zeppole / Chiacchiere

13. Frittelle / Zeppole / Chiacchiere

Fried sweet pastries, often dusted with sugar or filled with cream or custard.

Germany (Fasching)

Germany (Fasching)

14. Berliner / Krapfen

14. Berliner / Krapfen

Jelly-filled doughnuts, traditionally eaten on Fat Tuesday (Fetter Dienstag).

United Kingdom &

United Kingdom &  Canada (Shrove Tuesday)

Canada (Shrove Tuesday)

15. Pancakes with Lemon and Sugar

15. Pancakes with Lemon and Sugar

Simple, buttery pancakes made with flour, eggs, and milk, topped with lemon juice and sugar.